By Stephanie Cook, Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region, Saskatchewan

Stephanie Cook is the Director of Nutrition and Food Services for the Regina Qu’Appelle Health Region. She is passionate about food and nutrition and has spent the last two decades leading initiative aimed at improving nutritional well-being, such as programs for overweight children, developing healthy food policies and combating malnutrition in hospitalized patients.

Ringo Starr does not seem pleased with his hospital meal.

It’s hard to pinpoint that place in time when hospital food, once a cornerstone of treatment and recovery and considered wholesome and healing, changed in the public’s opinion to its current lackluster reputation. I suspect it has steadily declined as medical science and technological advancements began to trump food as the primary therapy and budget expense. I can’t say for sure what Ringo Starr was thinking when this photo was snapped in 1964, but if his expression is any indicator, I think he was less than impressed with what was on his plate. Fast forward more than half a century later and the perceived dissatisfaction with hospital food is only growing, with those consuming it not shy about sharing their discontent. Any patient with access to a cellphone can take a photo of their meal and post it online, sometimes creating nothing short of a media firestorm about the deplorable state of hospital food.

“But then, I wondered, is the food really that bad or is its reputation so tarnished by rhetoric that we never considered the possibility it could be anything different?”

For years I believed it too - hospital food sucks. In my time as a clinical dietitian I would nod, knowingly and sympathetically, as staff joked and patients complained about the food. What could I do? This is a hospital, a publically funded institution with an ever-shrinking food budget and fewer staff to prepare it. With pre-packaged out-sourced foods and fancy re-therm equipment taking the place of real cooking from scratch, of course food quality suffered. How could we be expected to strive for anything more than mediocrity? But then, I wondered, is the food really that bad or is its reputation so tarnished by rhetoric that we never considered the possibility it could be anything different? Was it possible that any attempts at quality improvement were simply going unnoticed, mired down by an impenetrable narrative? When I looked around I saw many patients cleaning their plates and asking for larger portions. Considering that the context is a hospital, where people are sick, away from home and family, in a strange and sometimes frightening environment; I had to wonder, is the food really that bad?

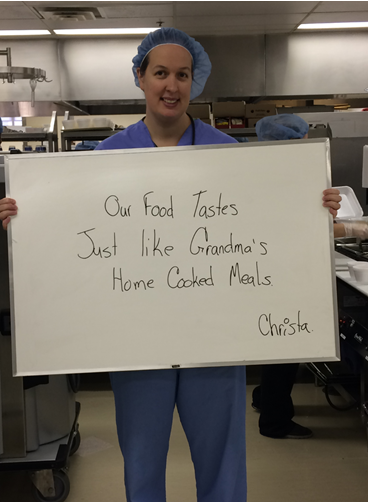

Admittedly, the food served in hospitals may not be exactly like our grandmothers. However, think about the task at hand - serving patients, most of them unwell, with different food preferences, coming from different cultures, and with varying nutritional needs — that’s no small feat! So when we put this in perspective, is the negative narrative that engulfs hospital food warranted? Or, is it simply a self-fulfilling prophecy? If we think that what we are about to eat is going to be terrible, then chances are it will be.

This issue bubbled to the surface in my health region not long ago when the results of the Canadian Malnutrition Task Force clearly identified how prevalent malnutrition is in hospitals and the many barriers that prevent patients from getting the nutrition they need. This led us to re-look at our food and assess is it really that bad or are we, hospital employees, so committed to the notion that hospital food is terrible that we unwittingly create yet another barrier that prevents patients from eating well?

4 dietitian students who were running the empty carts back to the kitchen to restock their supply of food (they had planned for about half as many participants!)

We devised a plan to try to measure this. The first step was surveying hospital staff to see what they thought. Predictably, staff rated the food negatively, describing it as unappetizing, lacking nutrition and of poor quality. As our second step, we decided to conduct a blind taste test in order to solicit more unbiased reviews. We advertised throughout the hospital that we were trialing some new items for our cafeterias and invited staff to sample six different entrees and rate their level of satisfaction (and ended up testing a total of 352 portions – reminding us to never underestimate the power of serving free food!). What we didn’t tell participants was that these were six entrees regularly served to our patients. The results were surprising with over 85% of participants indicating the entrées were “good”, “very good” or “excellent” for all quality measures (smell, taste, appearance, healthiness and overall acceptability). What’s more, over two-thirds of staff indicated they would purchase these entrees if they were offered in the cafeteria. That’s right, actually pay money for the very same meals we serve to our patients!

We have had a lot of fun sharing these results both within and outside of our health region. However, the greatest value without question has been sharing our findings with the food services staff. The positive reviews have helped validate what they know to be true — that every day they prepare and serve good food and they are proud of what they put on the plates.

This is not to say we don’t have opportunities to improve. In fact, listening to our patients was key to having our food so well-received. Patients have suggested they want to see more wholesome comfort foods made from fresh ingredients on the menu. While this sounds like a tall order, especially for hospitals that rely heavily on pre-prepared foods, there are a number of relatively simple fixes that can make a big difference. For example, in my health region we recently changed from buying pre-made broth soups to making them from scratch. We chose to focus on soup because it is a comfort food, fits most therapeutic diets and tends to be universally well-liked. We also saw an opportunity to pack in more nutrition using big pieces of vegetables, fresh herbs, noodles or rice and more protein. Not only do our patients approve but food services staff members feel good about making and serving it. We are also finding opportunities to include more locally grown foods on the menu, and spread the word to our patients and staff about our commitment to building a more sustainable food supply. Inviting staff to “come dine with us” and enjoy the patient meal of the day is another way to start engaging others.

“Bridging this gap is going to take more than just improving food - the healthcare sector needs a new commitment and an updated story of what goes on the plate, and how meaningful this can be to patients.”

In order to combat the long-time negative stereotypes surrounding hospital food, we must recognize the gap between where we are and where we want to be. Bridging this gap is going to take more than just improving food - the healthcare sector needs a new commitment and an updated story of what goes on the plate, and how meaningful this can be to patients.

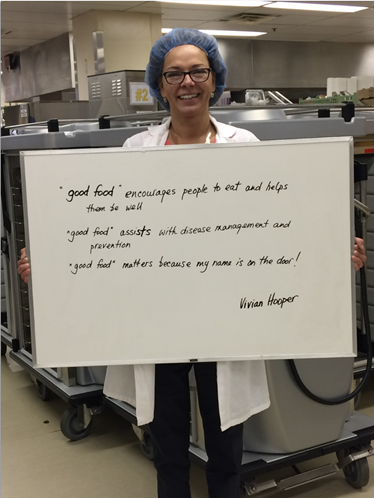

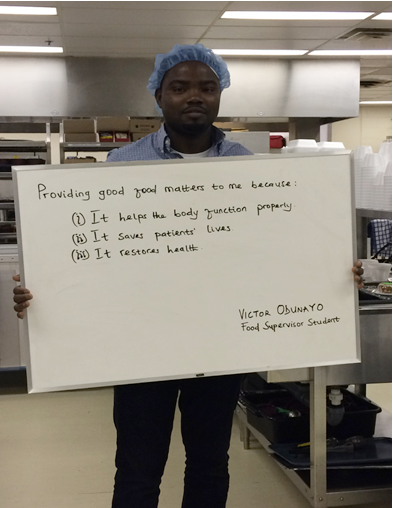

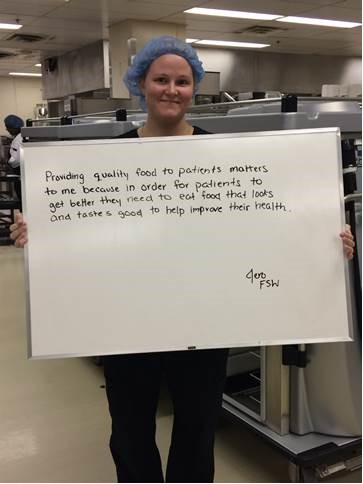

I asked staff at one of our hospitals the question “why does serving good food matter to you?”. No matter how they said it, the message was clear. Food is medicine and medicine heals.

Join me in creating this new story of hospital food!